Muslim girls express faith through hijabs, face judgment for beliefs in western world

Jacy Marmaduke

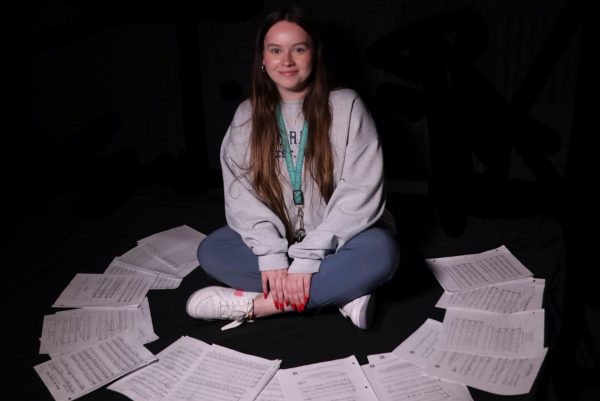

Reading the Qu’ran is a typical part of junior Salwa Mohamedaman’s routine at the mosque and at home. Salwa, who reads the Qu’ran for ten minutes a day, finished the entire book during her freshman year and ha memorized certain sections. She looks at the Arabic text alongside the English translation, the jumbled scribbles turning into understandable words.

It must be the sun that is stifling her. Bullets of light pierce through the fabric of her baggy sweatpants and long-sleeved jacket. The 96 degree heat piles up on her dark clothes, and the perspiration is just starting to form beneath her scarf. Her six-year-old sister, Mena, skips ahead of her, limbs bare in her one-piece swimsuit. A boy splashes into the Olympic-sized pool as she walks by, parachuting sprigs of water at the side of her face. The stares begin to gather around her like a cloud of gnats, burning into her scalp. Sunbathers glance up from their soggy copies of “Redbook” to watch her pass, to watch the girl who’s covered up at an outdoor pool. Tentatively, she dips a bare foot into the water. Even once she’s submerged in the lukewarm liquid, it’s so hot. Getting to the other side of the pool with her heavy arms and legs seems impossible. She tries to ignore the stares and keep her chin from drooping. They don’t bother her. It was her choice to come here. It must be the sun.

Junior Salwa Mohamedaman, a Sunni Muslim, has been wearing a hijab for more than three years. The hijab, a head covering that surrounds her hair and neck, represents repression and force for some women. But for Salwa, the hijab represents her freedom of choice. It’s an extension of her religion, the way she protects herself from physical judgment. It’s a constant and dependable reminder of her faith. It’s a decision she made at the age of 13 on how to live her life, manifested in a piece of cloth.

She isn’t alone. Sumiya Pirbhai, a bubbly sophomore with a story to relate to every conversation topic, has worn a hijab for four years. The two have been friends since the first day of Sumiya’s freshman year. Lost in the main hallway looking for a class, Sumiya hesitated in the quickly flowing river of students, her backpack hanging almost empty on her shoulders and her black hijab secured under her chin. Her glance had anxiously darted from one intimidating figure to another, until she saw Salwa. More specifically, Salwa’s hijab. Sumiya asked her for directions and then asked for her name.

Sumiya started wearing her hijab because she felt like she should. Every time a curious classmate asked her why she wore it, she used a default answer: “It’s a religious thing.”

“I didn’t get it at first,” Sumiya said. “I would wear it, and then I’d take it off when I got to school and put it back on the way home. But one time I thought, ‘I’m not going to take it off today, I’m just gonna see how it feels.’ And it actually felt … nice. When you talk to guys, they look at your eyes. You’re keeping your pride and dignity.”

The contents of their closets are different from other girls their age. They thumb through stacks of long sleeved shirts instead of skimpy tank tops, abayas (long, loose-fitting garments traditionally worn by Muslim women) instead of mini-skirts, arm warmers instead of earrings or necklaces. Women who dress in the hijab style can expose their feet, hands, and face. Nothing else.

Salwa coordinates her hijabs with her outfits — her light blue hijab with her light blue sweater, her pink rhinestone-studded hijab with her pink jacket. Folded into neat rectangles, they fan across her top drawer in fabric rainbows.

While they’re at home, their hair may be loose, their arms bare. The rules of dress only apply while in public or in the presence of any male who isn’t a blood relative — any boy who could conceivably fall in love with them. If a male neighbor pops in to say hello, or a friend brings her younger brother over with her, the hijab comes back on — a series of pulling and pinning that only takes a few minutes. Boys, especially young boys, don’t seem to get that they shouldn’t see the girls without their hijabs on.

“It’s like we’re off-limits. Sometimes they’ll glance over, see [my hijab] and then look away. I don’t want a guy like that looking at me anyway.”

They pray five times daily. Salwa said that performing the prayers makes her feel “like all my problems weren’t as big as I thought.” The times of the prayers change according to the position of the sun, but the early afternoon prayer, Dhuhr, always falls in the middle of the school day. Salwa performs the prayer in the front office, surrounded by beige cabinets and copy machines. Closing her eyes, she begins to recite memorized sections of the Qu’ran, her small voice ringing amongst the phones. She stands with her palms lifted, then clasped, bends over with her hands on her knees, straightens again before falling with her head and hands to the nubby blue carpet. Thoughts of her day, her school and her family drain from her consciousness like sediment from filtered water.

There is never a time when their religion is not a part of their lives. But it isn’t the only part of their lives. Western influence has inevitably taken its course. Salwa’s family eats fajitas or chicken fried steak for dinner some nights, made with Halal meat, which meets Muslim dietary guidelines. She watches “CSI: Miami” on Mondays. Even though her shoulder length hair is covered by her hijab, she still cares about how it looks.

“One girl was like, ‘You could go bald and it wouldn’t matter!'” Salwa said. “But it does matter. I don’t want to be bald. I’ll straighten my hair sometimes, and I do it for myself. I just like to do it for me.”

The stares are always part of their lives. Surveys estimate that there are anywhere from one billion to two billion Muslims in America, but the sight of a woman wearing a hijab still evokes a reaction. It’s usually small, the holding of a glance half a second longer than necessary, just a little more hesitance in a stranger’s approach. Salwa said that the reactions no longer surprise her. People fear what is on the other side of the closed door. In America, the door to Islam remains closed.

“Outsiders don’t see it the way we do or have the insight that we have, and they don’t try to understand,” Salwa said. “They just try to impose their ideas on us.”

Front page stories of bombings and shootings committed by Muslim extremists leave stains in the mind that are deeper and harder to erase than more positive impressions.

“People interpret the Qu’ran different ways,” Salwa said. “They see what they think is right, and they focus on it. It’s obviously what we see as wrong, but they … they think they’re on the right path.”

America is Salwa and Sumiya’s home, but their religious origins lie in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Both have made trips to Mecca to experience first hand the roots of Islam, the tree that has branched so far across the world. When they go there, they get to see the city that they pray toward 1,825 times a year.

“You don’t feel like an outsider,” Salwa said. “Everybody is just like you.”

Islam has spread from Saudi Arabia to virtually every region of the earth. The girls were born in America, but Sumiya’s family is from Pakistan, and Salwa’s family is from Eritrea, a tiny east African country bordering Ethiopia. Border conflicts have taken their toll on Eritrea.

“I came to America because there was a war that I couldn’t bear,” said Abdu Mohamedaman, Salwa’s father. “This is the land of freedom. [I wanted] my children to have that.”

More than half of Eritrea’s population subsists on $1 or less per day, making it one of the world’s poorest countries.

“It’s a place I could visit but not live,” Salwa said. “Whenever I go there, I feel rich. The neighborhoods are dirt. My cousins go out and play with it as if it’s sand, but you know the difference.”

Every day, they stand in front of their bedroom mirrors to put on their hijabs. Today, the mirrors reflect members of a religion that seems to be outnumbered. Tomorrow, things could be different.

“The way we dress, the way we act, the way we talk — we contradict everybody else’s beliefs,” Salwa said. “It makes us stick out — for the good and for the bad. Some people learn and evolve, but some people don’t. I don’t think people are to blame, that’s just the way they are.”