Triumph out of tragedy

Junior uses football to overcome death of a family member

Mikey Gutierrez was working out with the football team during fourth period. He finished his set of squats and looked up to see linebacker coach Jason Hinkelman. Hinkelman handed Gutierrez a pink slip, and he couldn’t help but notice that the usually enthusiastic coach was troubled by something.

His feet couldn’t carry him fast enough from the weight room to the freshman center.

“All the note said was that my dad needed to see me,” Gutierrez said. “I walked into the front office and saw my dad trying hard not to cry. He’s a tough guy and I had never seen him cry before. He told me that my mom had passed away, and I just felt disbelief. I had to hear him say it a few more times for me to process that my mom was gone.”

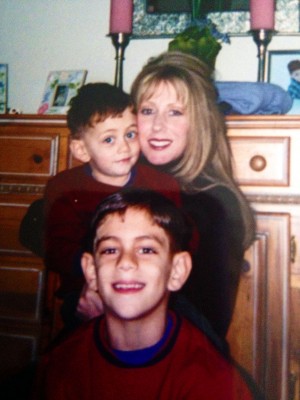

Gutierrez’s mother, Melanye Gutierrez, had died of a self-inflicted gun shot in their house on April 25, 2013, just one day after returning from a month-long hospital trip. She left behind a husband, Mikey and three other children.

“I broke down and just started bawling,” Gutierrez said. “When we walked back to the fieldhouse to get my things, I was angry. I punched lockers in the locker room and was just in shock. When I got home, my grandma was on the front porch with all my neighbors around her trying to comfort her. She was so emotionally distressed and was crying so hard. I had to tell my siblings what happened when they got off the bus.”

Gutierrez clearly remembers the last encounter with his mother. It was the night before she committed suicide.

“I told her I just wanted to talk to her because I hadn’t seen her in a month,” Gutierrez said. “We laid down facing each other on her bed and I asked her what she had been up to. She wouldn’t answer me and … she kept telling me to go upstairs, so I did. I told her I loved her, and she told me that she loved me too. The last thing I remember is her locking the door.”

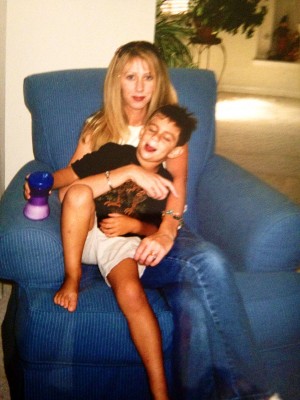

Gutierrez’s childhood friend, junior Lincoln Chambers, has fond memories of spending time at the Gutierrez household.

“His mom was the friendly neighborhood mom,” Chambers said. “I remember in 7th grade, she bought me clothes that I needed for athletics when my mom was out of town. She somehow found out my size and ordered them online for me. She was so hospitable and an extremely nice person. She treated us [Mikey’s friends] as if we were her own kids.”

Afterward, depression and guilt quickly set in for Gutierrez, and he found it hard to focus on daily activities, leading to over-thinking and a failed freshman algebra class.

Every time I pass it, I just stare at it. I look at the little room where my mom slept. The memories of that house are all happy except for the one that happened that day. — Gutierrez said when describing his mood towards his old house

“Sometimes I wonder if I would’ve stayed in that room, then I could have prevented what happened,” Gutierrez said. “That’s what hit me the most in depression, and I had to realize that there was nothing I could do. My grandma helped me come to terms with that, but there isn’t a day that goes by where I don’t think about my mom. I daydream in class and think of ways I could have prevented it.”

While the guilt has slowly faded, the nature of his mother’s death mixed with other family tragedies, like the two-day time span of his grandfather’s passing and his uncle’s murder, have made the recovery process even tougher.

“It’s only just recently that the pain has lessened,” Gutierrez said. “During Christmas break this year, I had suicidal thoughts. I couldn’t deal with it. I didn’t know what to do. Seeing my grandpa suffer got to me … I loved that man to death. Watching my grandma cry made me depressed to the point where I almost did it.”

As Gutierrez struggled with suicidal thoughts, his friends struggled with what to do. Junior Daniel Kim, another childhood friend of Gutierrez’s, noticed the pain his friend was enduring but found it hard to help.

The old house is only about two miles away from where I live now, and my friend Lincoln lives really close to it. — Gutierrez said. Gutierrez's old house is only a few houses down from Chambers' house, so he frequently feels the slight twinge of pain when he passes it.

“Right after it happened, we [Mikey’s friends] would always ask if he was OK,” Kim said. “He just wanted to be alone, but we always asked if he wanted to talk. He mainly just secluded himself, and we didn’t want to seem like we were digging into his business. We realized the best thing to do was to let him cope with it and not force anything.”

Gutierrez’s seclusion from those who wanted to help him the most made for a sudden shift in his personality from energetic to awkward in his social interactions.

“Secluding myself from people made me … hard to keep a conversation with,” Gutierrez said. “Everyone would be happy and laughing, and then I’d just stop laughing all of a sudden. People felt like they couldn’t say certain things to me because they didn’t want to offend me, which got on my nerves.”

While his social life struggled, Gutierrez was forced to deal with numerous responsibilities. With his mom gone, Mikey has taken on the role of the second parent.

“Now I have to get up early and make breakfast because my dad works three to four jobs,” Gutierrez said. “He sometimes doesn’t get home until three in the morning, so it’s my job to wake up everyone in the morning and get them ready for school. When my dad’s gone, I’m the man of the house. That’s why I have less free time, because when he’s at work I have to stay home and watch my siblings.”

All the stress and responsibilities wore Gutierrez down. He needed someone to vent his frustrations to, someone he could trust. That person turned out to be head football coach Brian Brazil.

“He came to talk to me about possibly moving away from Hebron,” Brazil said. “I let him know that if anything was going on, then he should know he had a lot of support coming from the football program. I think it helped him a lot. He was struggling with the ‘Why?’ and I told him that we will never know why. Those are things you just can’t understand. I told him that his mom loved and cared about him. I encouraged him and let him know that he would get through it.”

There was one outlet that Gutierrez could have every day: football. He loves the game, and it allows him to both release his frustration and forget about the outside world.

“I look forward to it every single day and it takes away the stress of school,” Gutierrez said. “If I was borderline in a class, football would help me take my mind off it.”

Brazil also noticed the positive effect the game has had on Gutierrez.

“Since our first meeting, I’ve seen more of an ease about him,” Brazil said. “He seems like he’s able to cope with it better. Football is a good release, whether it be through working out or just getting your juices going.”

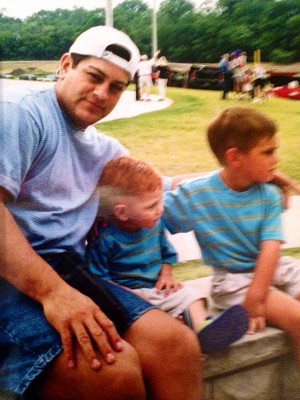

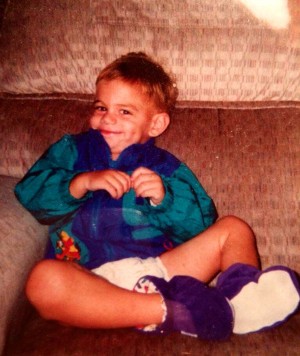

Gutierrez’s love for football has been noticeable since his elementary school days. He played the game in the streets of his neighborhood with Kim, Chambers and numerous others for hours on end. Distancing himself from the game sophomore year as he battled with depression only worsened his condition. Now, he strives to be a varsity starter on the football team, with the motivation to make his mother proud driving him every day.

“During the coin-flip, I’ll separate myself from everyone on the sideline and get on one knee and pray,” Gutierrez said. “I did that a lot last season, and I would always think of my mom. The adrenaline then rushes through my body and I’m ready to play. When I’m home not playing video games, I watch film to see what I can improve on. Sometimes I run routes and have my dad throw the ball to me. I go to the weight room in my apartment complex when I can or call up my friends to meet me at Hebron.”

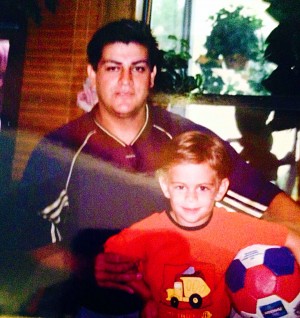

Despite his busy work schedule, Gutierrez’s father, Miguel Gutierrez, found time to attend his son’s JV games last season.

“My dad hit rock bottom after what happened,” Gutierrez said. “He works six days a week and he can’t take any vacations. For him to find ways to make my games was huge to me. I owe him everything. I don’t even know how to repay him for all he’s done for me.”

Although football gave Gutierrez an oasis within the real world to relax, he still didn’t have anyone his age to vent to. His social distancing had made his friends harder to talk to, and he couldn’t express to them what he was really thinking. Then, Gutierrez began talking to, and eventually dating, junior Abbey Yates, a girl he had been fond of since freshman year.

“I vented everything to Abbey,” he said. “She helped me through my depression, and she was the main reason why my suicidal thoughts disappeared after Christmas break. When I told my ex-girlfriend about my own suicidal thoughts, she didn’t care. I was so worried about having someone to talk to that I kept her around longer than I should have. That was bad for me, which is why I appreciate having Abbey to talk to so much more.”

With a renewed passion for football and someone his age to confide in, things are getting better for Gutierrez. But the pain still lingers.

“Every time when I’m in the weight room, I remember that day,” Gutierrez said. “When I rack my weight, it triggers a flashback because that’s what I was doing when Coach Hinkleman gave me the slip. When someone makes a suicide joke, it strikes a nerve with me.”

Brazil knew that the recovery process would be a long one for Gutierrez.

“I told him there will be days when something will trigger bad memories, and I advised him to just come see me when he had those feelings,” Brazil said. “I’m not going to sit there and belittle him or make him feel bad because I’m aware of what happened in his life. I’m just trying to help him cope with it the best way I can. When you have people that care about you, it makes a difference.

Chambers has come to respect his friend for how he handled the situation.

“Having to help take care of three other siblings takes a lot of strength, and he’s helped his dad raise them,” Chambers said. “He’s taken a lot of responsibility and handled it well. It takes a really strong guy to cope with what happened and be there for his family.”

Spring football started a few weeks ago, a bittersweet moment for Gutierrez. His favorite activity in the world started up again, but he was also reminded of the two year anniversary of his mom’s passing. The tragedy is something he will never forget, but it has profoundly changed his views on the world and the people around him in a positive way. He is ready to put the struggles of his past behind him and put energy into future triumphs.

“Mikey may be able to help other people cope because I think God uses the burdens we have in life to help other people,” Brazil said. “I think that’s something Mikey is going to be able to do. He’s going to be able to help others get through similar problems and become a blessing to them.”

Senior Matthew Rutherford is the sports editor, and this is his third year on staff. He enjoys playing almost any sport and is also very sarcastic, which...